In “Should Tattooing be Taboo?” April 2015, Spanking FIT examined the controversy surrounding modern-day tattooing practices and associated health risks. Legitimate concerns raised led us to embark on our “Healthy Body Art for the ‘Boys’ & ‘Girls’” series containing exercise sets designed specifically to enhance physical attractiveness, but without the potential hazards of unnatural “body art” such as tattoos and piercings. Previous segments introduced simple exercises for women and men to acquire “Venus Dimples” (Part I), for enhancing the “Butt” (Part II), for developing “Broad Shoulders (Part III), for acquiring an impressive “Chest” (Part IV), and for development of upper arm muscles “Biceps & Triceps” (Part V).

In our current healthy body art segment, Part VI, Spanking FIT examines the science behind lower body development concentrating on the legs. Healthful consequences include improved locomotion, better appearance and posture, and cardiovascular fitness. We begin with a brief review of the leg muscles with a description of their function:

The muscles of the legs

Principal leg muscles may be divided into three major groups: the hamstring group (back of thighs), the quadriceps group (front of thighs), and the calf muscle group (back of lower legs).

Hamstring group (back of thigh)

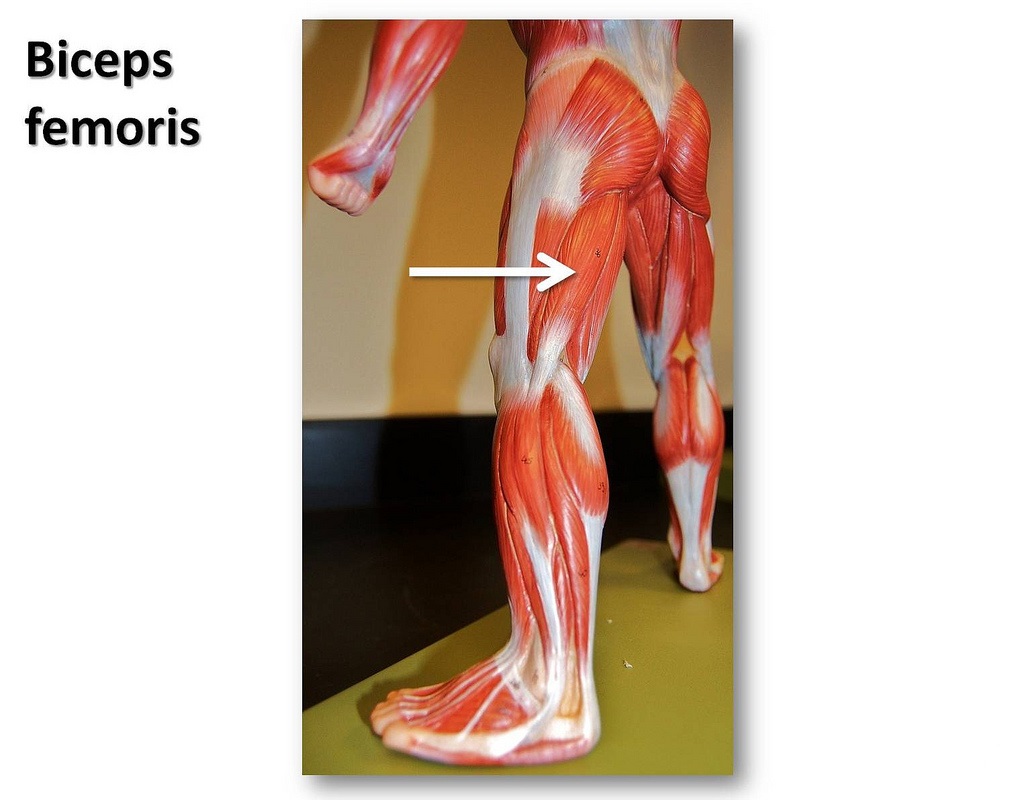

The largest of this group is biceps femoris. It primarily functions to flex the leg at the knee joint, and to extend the thigh at the hip. When well-developed, it also enhances female and male sexuality. Biceps femoris is illustrated below:

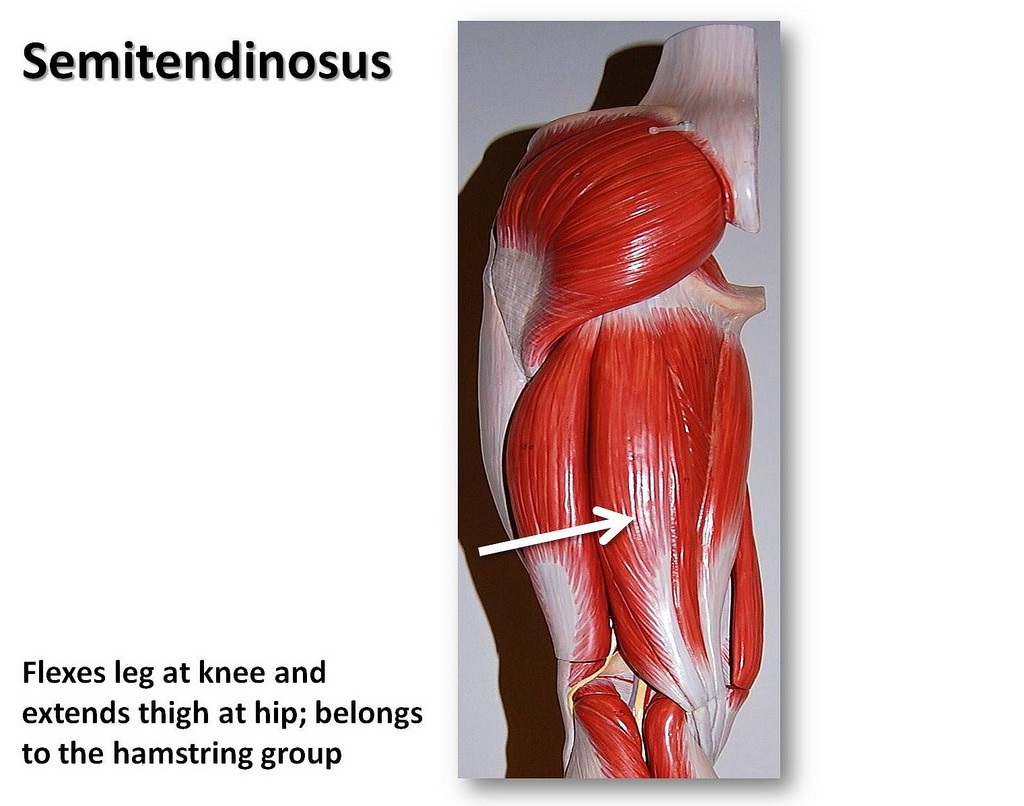

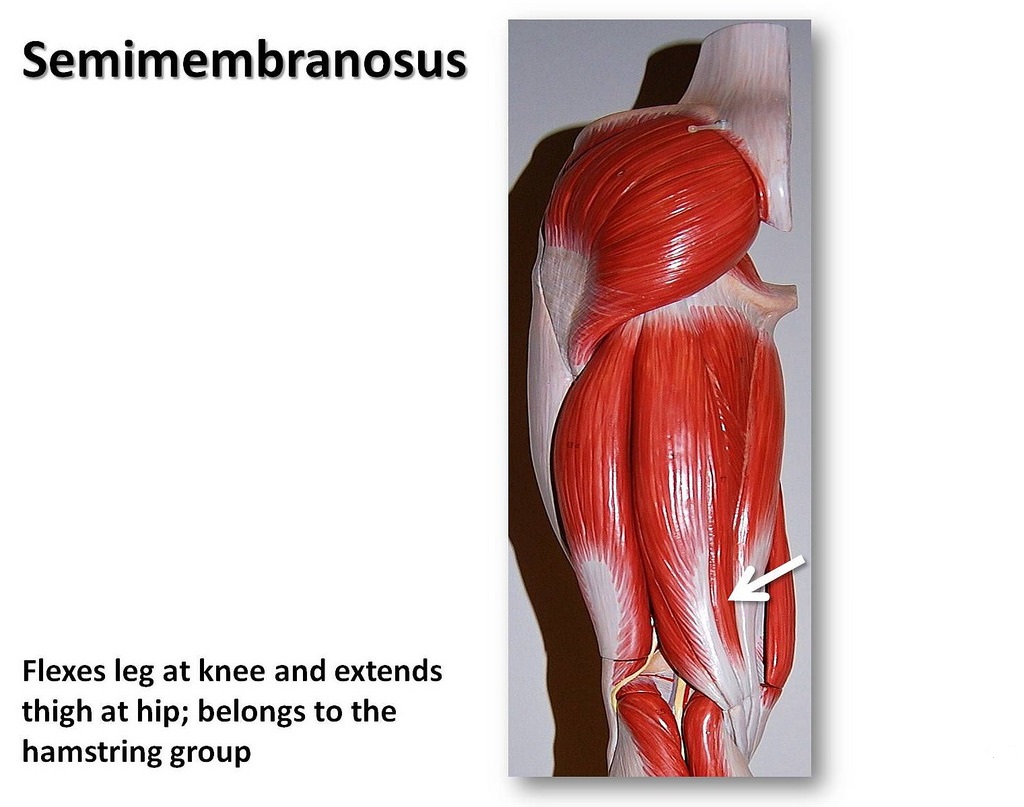

Semitendinosus performs a similar function to biceps femoris, as does semimembranosus. The latter also assists in rotating the tibia (shin bone).

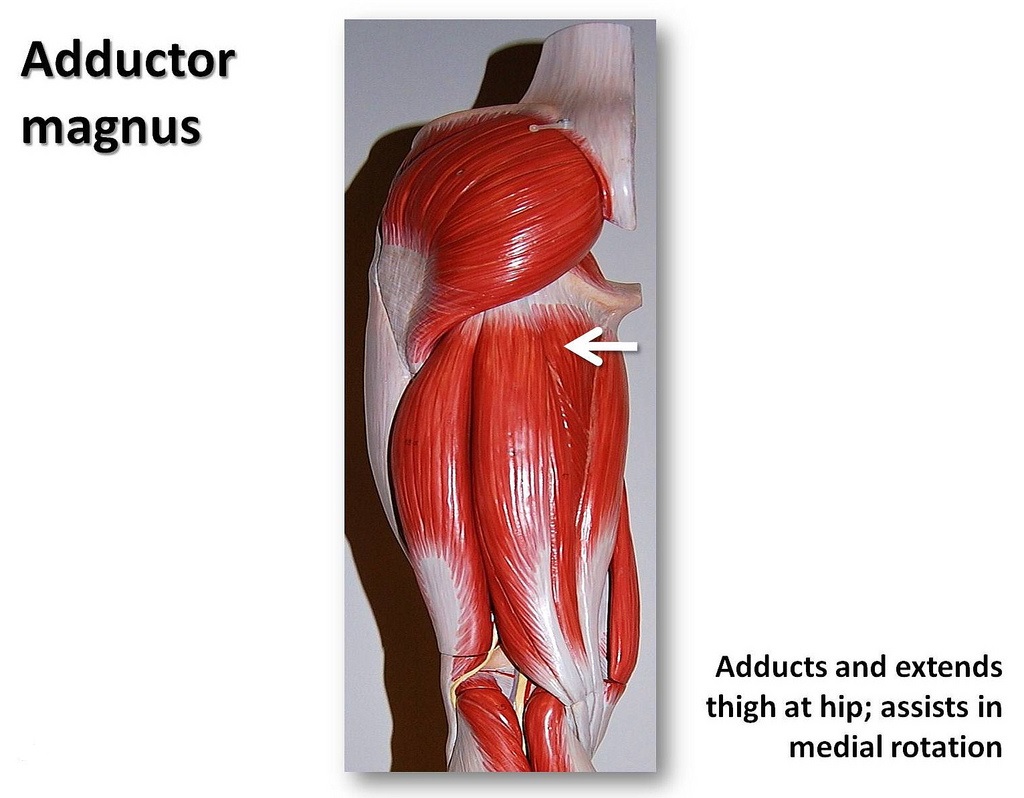

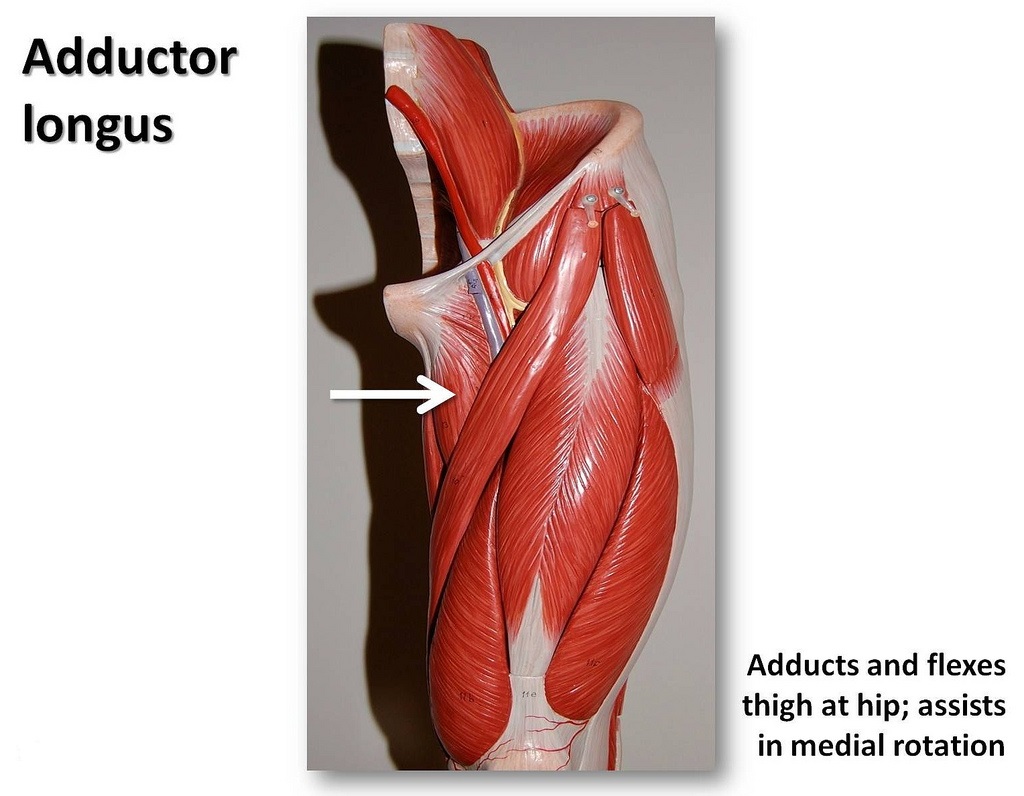

Adductor magnus is one of the largest muscles of the human body. That’s the main reason that leg muscle workouts yield wonderful cardio-vascular fitness. As its name implies, its primary function is adduction (movement towards body center) of the thigh at the hip. Its thin partner adductor longus, performs similarly.

The quadriceps group (front of thigh)

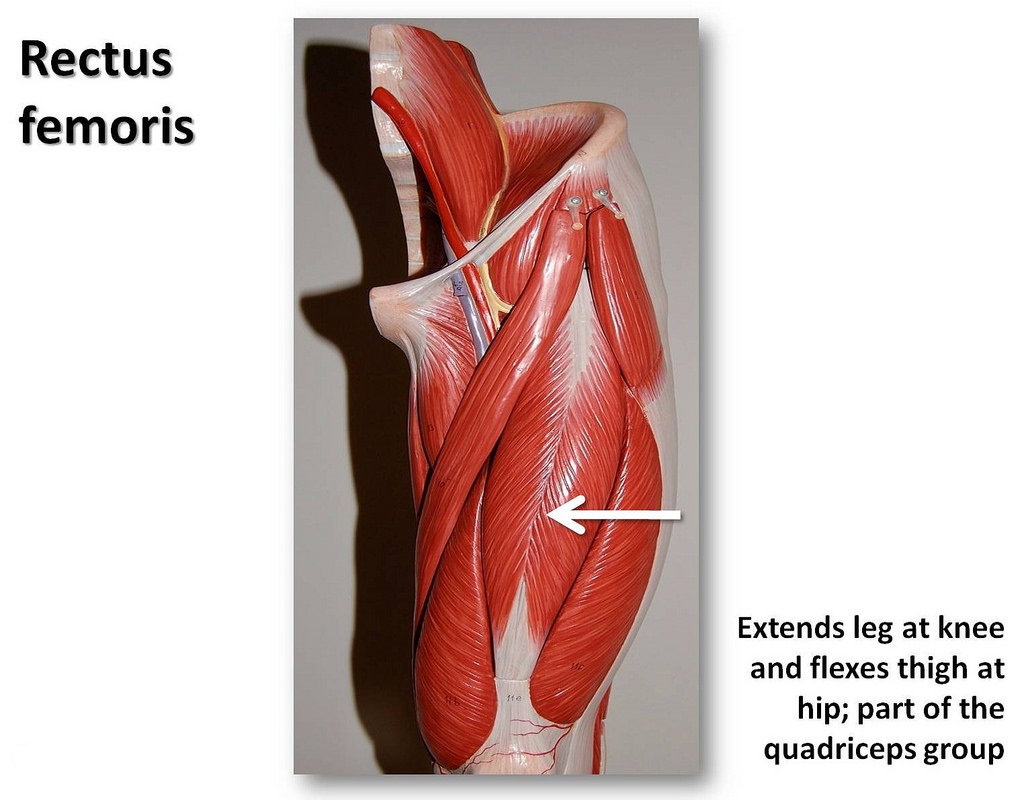

Functioning in a manner similar to its partner biceps femoris, rectus femoris, located in front of thigh, also extends the thigh at the hip, and, to a lesser extent, flexes the leg at the knee.

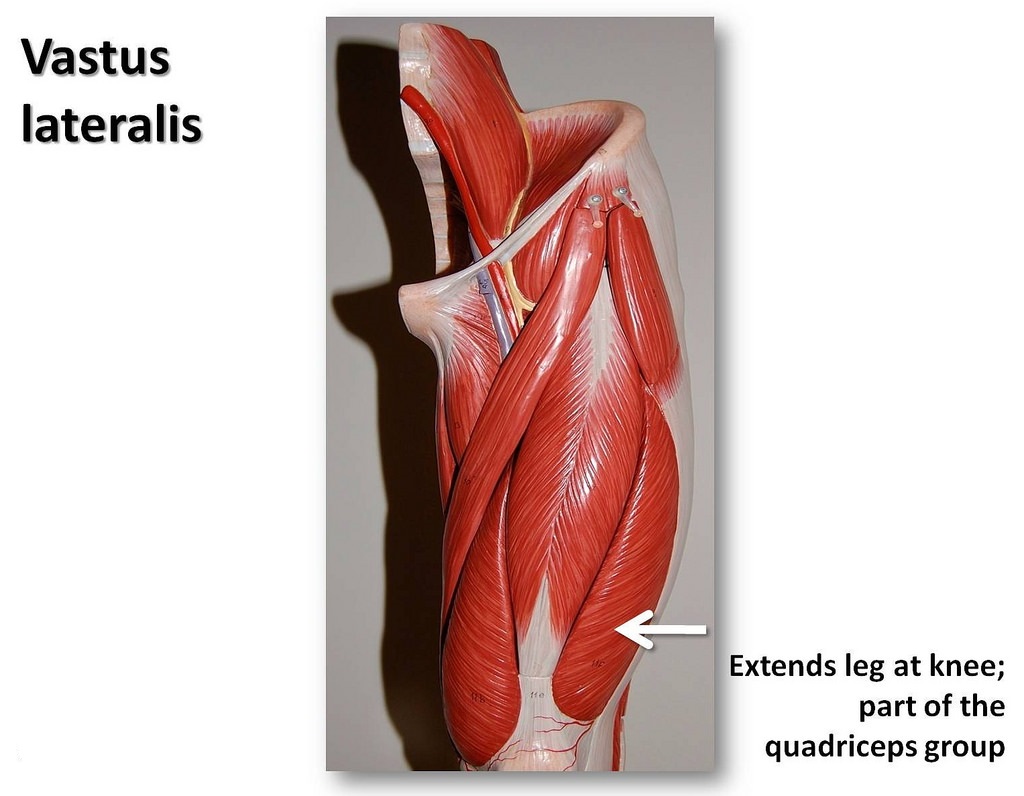

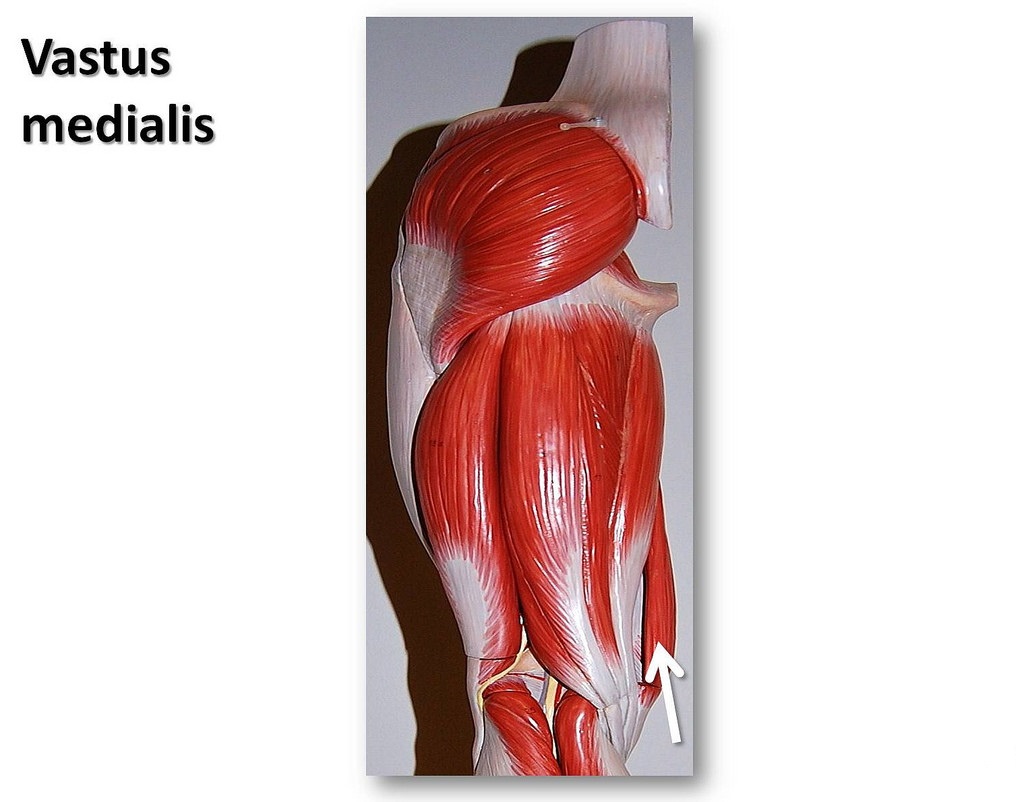

There is also vastus lateralis (largest of the quad muscles), vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius. All function primarily to extend the leg at the knee.

Vastus intermedius

Calf muscle group (back of lower leg)

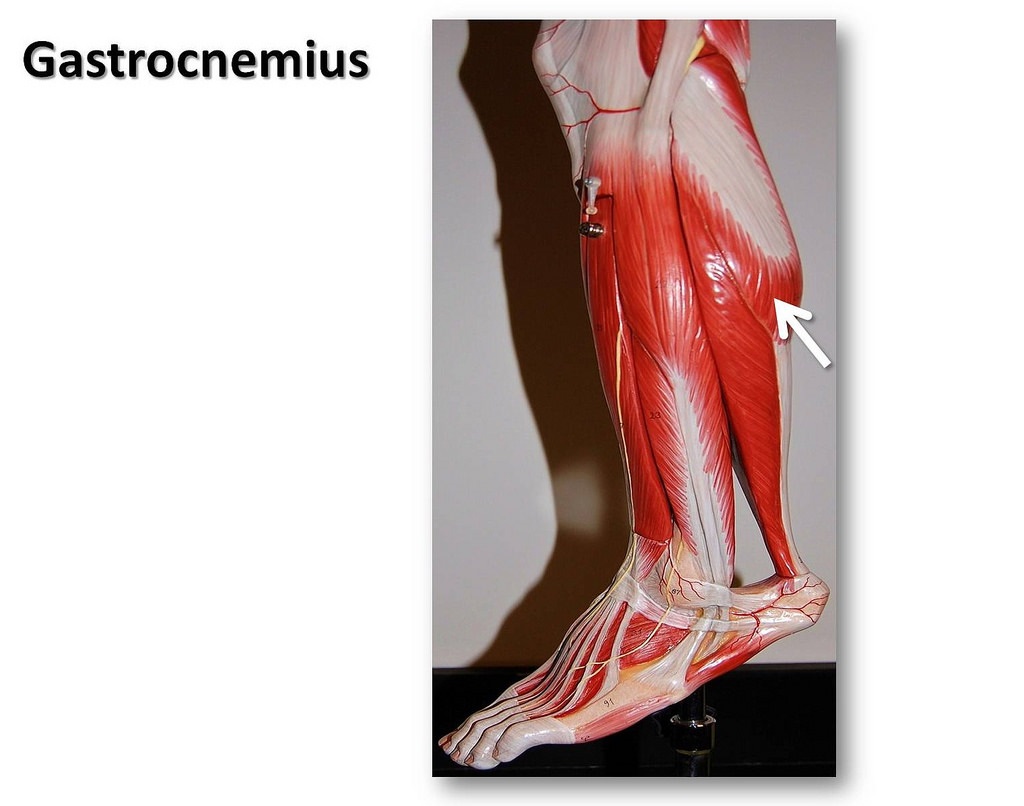

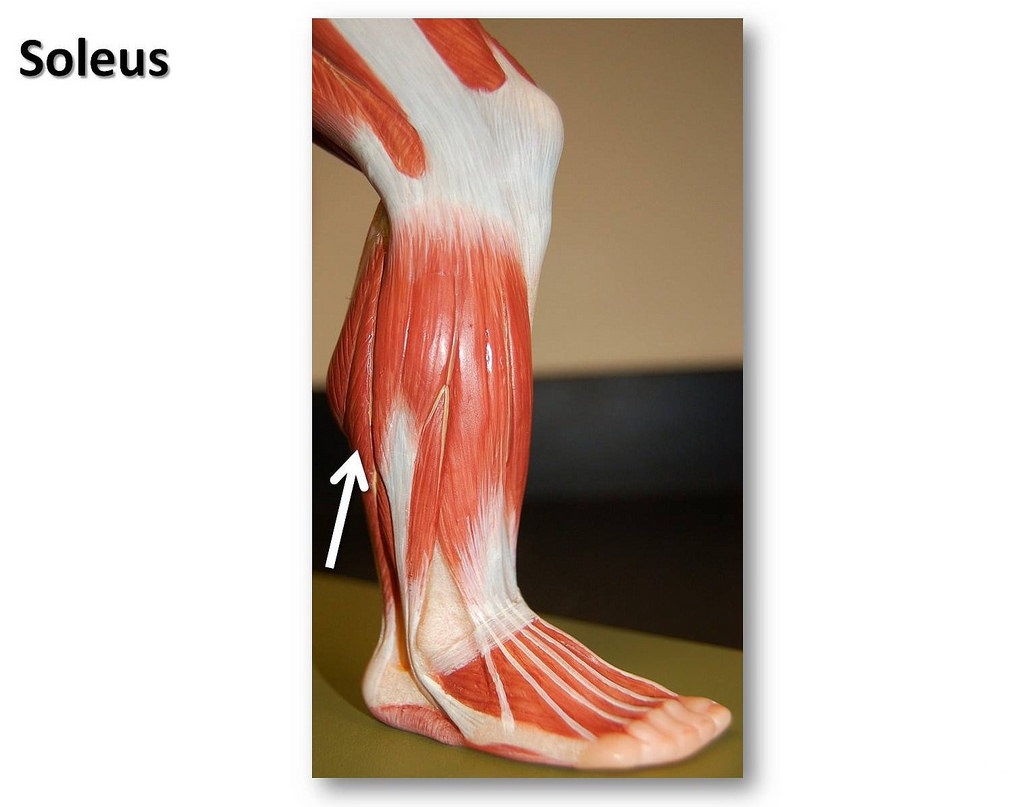

Gastrocnemius flexes and extends the foot, ankle, and knee. Soleus is the flat muscle lying beneath it. Plantaris, when it is present, also augments gastrocnemius. Plantaris is completely absent in a large percentage of the population, so that it is quite possible your legs are missing them. (Readers may recall the note about “bio-individuality” made in the Spanking FIT ABOUT US category, which you may wish to review.)

Leg Workouts

There are a number of effective leg muscle exercises, the most common of which are presented in the table below. Each has associated benefits and risks. Please review it and give me your feedback based on personal experience. (As you know, unlike most med web sites, we encourage collective contribution on the part of readers.)

| Workout | Involved Muscles | Benefits | Risks |

| Walking | calves, quads, & hamstrings |

|

|

| Running (track or treadmill) | same as above | same as above | all of the above incl. shin splints (tears in muscle around the shin bone.) |

| Bicycling (dirt, roadway, or exercise machine) | above plus hip flexors, glut max, foot muscles (plantar flexors & dorsiflexors) | same as above | all of the above; however, decreased risk of groin strain, achilles tendinitis, & plantar fasciitis. |

| Squats (with or without weights) | same as running plus glutes & abs | bulky development of muscles depending on weight used & the no. of reps. |

|

Walking is among the simplest and most effective leg muscle exercises, especially when non-bulky development is desired. However, as previously noted in the table, knee strain is a common consequence of walking, especially if one wears inappropriate shoes. Running carries similar risks. In “Running Shoes, Don’t Leave Home Without Them!” Nov. 2014, Spanking FIT presented several tips on how to prevent “runner’s knee”. They included wearing proper shoes at all times, even when not running! In addition, groinal strain may occur, especially if one frequently walks up hills or carries weight along. Refer to “Prevent Groin Injury & Inguinal Hernia“ Spanking FIT, Oct 2014, for a few tips on that subject.

It is not uncommon for cycling enthusiasts to report knee injury especially as a consequence of sporting competition. Nevertheless, cycling is often recommended by therapists for rehabilitation of knees following injury, or even after knee surgery. It is also prescribed for chronic knee conditions such as osteoarthrosis (non-inflammatory bone disease caused by “wearing down” of cartilage and sometimes referred to as osteoarthritis). The unproven theory behind this is that cycling “nourishes” joint cartilage (refer, for example, to cartilagehealth.com). Spanking FIT conducted a search for serious medical research which refutes or confirms that hypothesis, but came up empty. It appears that there may presently be none. The good news is that clinical trials are under way in Oslo, Norway for purposes of evaluating the efficacy of both cycling and strength training with weights on knee osteoarthritis patients. These trials are scheduled to be completed in 2025, with preliminary results to be released later this year. (See:”Efficacy of exercise on physical function and cartilage health in patients with knee osteoarthritis”; clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT1682980.) In the meantime, a safe rule is to always practice moderation in exercise, and to “listen” very carefully to how your body responds to all exercise forms including the above.

Last but not least comes squatting, both with and without weights. Variations include “full squats‘, “half squats“, and even “quarter squats“, depending on the angle that the upper legs form with the vertical line, vertex at the knees. The squat is famously one of the three lifts performed in the strength sport known as “power lifting“. In the latter, the top surface of the legs at the hip joint is positioned below the knees (“deep squat“).

The fact that knee injuries do occur as a result of participation in non-professional sports, and even in non-sporting squatting activity, is apparent from the 2004 publication by G.I. Dross et al: “The causes and mechanisms of meniscal injuries in sporting and non-sporting environment__” which was published in the appropriately titled journal, The Knee. In it, researchers studied 392 knee injury patients ranging in age from 18 to 60 years old with current meniscal injury, but with no prior injury history. Although 32% of all the injuries were sports-related, weight lifting per se was not identified as being causal for any. Nevertheless, a full 15% of all the knee injuries were attributable to squatting in every day activities, especially in the act of ascending from a crouched position.

Individuals who engage in squatting as a component of intensive strength training with weights, may be at increased risk of injury. In “An overview of strength training injuries, acute and chronic” by M.E. Lavallee et al. published in Current Sports Medical Reports, 2010; 9, 307-13, researchers carefully documented sports-related injuries that resulted from squatting. They included rectal prolapse (where a portion of rectum slides outside of the body), lower lumbar injury, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, acute rupture of the quadriceps or patellar tendon, and ankle joint dislocation. Again, keep in mind that all recorded injuries were a consequence of intensive sports-related strength or resistance training and not casual exercise.

Can squatting lead to serious degeneration of the knees over the long term?

The question of whether or not squatting exercises can, over a prolonged time period, lead to degenerative knee injury is currently at the center of much controversy in the Sports Medicine arena. Some researchers such as H. Hartman of Frankfurt, Germany, feel strongly that squatting (especially deep squatting when the legs are positioned below the knees) “does not present a risk of injury to passive tissue” and that “concerns expressed by some about degenerative changes are unfounded” (See:”Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral columns with changes in squatting depth __”, by H. Hartman, et al., Sports Medicine, 2013, 43:993-1008 . Work by B. Hamill: “Relative safety of weightlifting and weight training” published in the Journal of Strength Conditioning Research; 1994, 8:53-7, is cited to support Hartman’s claim. Dr. Hamill, in turn, references an even earlier study conducted in 1980 by Fitzgerald and McLatchie which claimed to have “dispelled the myth” that degenerative joint disease (osteoarthrosis) or simply O.A., occurs more frequently in weightlifters than in the general population (See: “Degenerative joint disease in weight lifters, fact or fiction? in British Journal of Sports Medicine; 14, 97-101 by above authors.) In the latter, a sample of twenty five Olympic and power lifters, ranging in age from 24 to 49 years old and who had practiced for an average of 17 years, were examined both clinically and radiologically. It was revealed that 5 out of the 25 or 20% suffered degenerative joint disease. Comparing their finding with that of another study indicating that the prevalence of osteoarthrosis is 38.3% for males roughly same age (“Osteoarthrosis. Prevalence in the Population and Relationship Between Symptoms and X-ray Changes” by J.S. Lawrence published in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 25:1-23), the researchers concluded that “long-term weight lifting does not produce inevitable joint degeneration”. However, upon careful scrutiny of the previous analysis, Spanking FIT discovered what may be a serious flaw in it. According to their reported findings, at least 4 out of the 25 or 16% suffered osteoarthrosis specifically in the knee area (either in the femoro-tibial articulation or in the patello-femoral joint). Moreover, the seriousness of their condition was rated Grade 2 or higher using the identical rating system that Dr. Lawrence and his associates used. Lawrence reported only a 5.6% incidence rate for knee O.A. for similar age and same grade category. Spanking FIT next performed a statistical “Fisher’s exact test” based on a contingency table derived from the previous results and found that the incidence rate for knee O.A. was significantly higher in the weight lifters than the general public at a non-conventional 0.0771 significance level. I realize that most readers are not statisticians, but these findings are significant enough to at least call into question the claims of all the previously mentioned researchers who dismiss the possibility of long term knee O.A. injury for weight lifters.

Finally, there’s an important and relevant study which deserves to be cited: “Knee osteoarthritis in former runners, soccer players, weight lifters, and shooters” by U. Kujala, et al. published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, 1995; 38 issue 4:539-546. In this one, 117male former “top-level” athletes aged 45 to 68 years old were examined and the prevalence of tibiofemoral and patellofemoral O.A. recorded and compared among the different sports participation groups. By performing a statistical Chi-squared test for independence followed with a post-hoc Marascuillo test, Spanking FIT independently confirmed that weight lifters are at increased risk from O.A. in comparison to shooters (the control group).

It is important to keep in mind that all results are derived from data on professional weight lifters only, so that it is not at all clear whether or not incorporating moderate squatting exercise into one’s exercise routine places one at increased risk for long-term degenerative knee injury. As previously mentioned, some “experts” assert the opposite.

The ancient Hindu art of squatting

Whether it is out of a concern about long term joint or spinal injury, or simply out of a desire to combine strength training with aerobic exercise, a growing number of the fitness-conscious are including the Hindu Squat in their regular workout routine. Hindu squats are a variation on the traditional squat adding elements of eastern Yoga to the more intensive squatting exercise favored by the West. Hindu squats are generally performed with feet shoulder width apart while keeping the heels raised. Toes and knees should point forward. Keeping her body weight on her toes at all times, the subject then lowers herself down by bending the knees (back upright)until her thighs are parallel to the ground. Her arms should either hang down or be moved behind her buttocks. Next, the subject quickly stands and extends her arms straight in front of her body or up. For your benefit, I have included this well executed instructional video:

By comparison to traditional squats, Hindu squats provide for a more rigorous quadriceps workout, and also may promote greater knee joint mobility. Their rhythmic motion facilitates repetitions with resulting cardio benefits.

Conclusion

Walking, running, bicycling, and squatting (with or without weights) constitute important ways to develop the muscles of the legs. Each has benefits and risks. Walking is the easiest method of getting outstanding results with minimum risks to other portions of the anatomy. Running, which presents higher risk, also provides enhanced cardio benefits. Bicycling yields muscle development plus cardio benefit, and may also help in maintaining joint health and assist in injury rehabilitation. (Confirmation of claims await completion of relevant clinical trials.) For building bulk musculature, nothing beats squatting with weights. However, contrary to the pronouncements of many sports “experts”, evidence does exist that it may be detrimental to joint health over the long run, if practiced intensely. Hindu squatting may be the safer alternative.

I hope that you also found this recent Healthy Body Art series segment informative. Hopefully, it will prove helpful toward advancing your health and beauty goals safely, and without the unnecessary risks posed by tattooing and piercings . If you haven’t already, please read “Healthy Body Art (Part I) in which we explain how women and men alike can develop those much coveted sexy indentations in the lower back known as “Venus Dimples“. I look forward as always to your feedback. Cordially, Doctor Garrett

Save